By the time Gachiakuta’s white-haired protagonist is hurled into its festering underworld, dumped like garbage into the detritus of a caste-stratified society, the fall feels inevitable. He had always lived socially, spatially, and spiritually adjacent to the trash heap, and the obliviating void of The Pit was merely the logical endpoint of a life marked by othering, suspicion, and a cultural rot disguised as law and order. Japanese mangaka Kei Urana’s story may be built on a mountain of waste, but at its core, it’s about class. About what happens when society draws a hard line between the people it deems worthy and the ones it would rather pretend don’t exist.

Rudo, a child of the slums, is the inheritor of ancestral shame and the progeny of people deemed subhuman. These “tribesfolk,” descended from exiled criminals, exist in a zone of perpetual contamination. When something, or someone, no longer fits into the narrative of purity and progress, they’re tossed into The Pit.

Much like in Bong-Joon-ho’s Parasite, where the faint but inescapable “smell of the poor” becomes a sensory marker of class that offends the wealthy, Gachiakuta uses trash and filth as the lingering evidence of those made inconvenient to society’s delusions of cleanliness. In both, the idea of “purity” becomes weaponised, turning the impoverished into something grotesque, to be hidden, expelled, or dropped into a pit when they go against the moral hygiene of the powerful.

This dystopia offers a diagram of the colonial gaze. In the historical machinery of imperialism, the colonised were marked first by their utility, and then by their abjection. Once stripped of national belonging and transformed into subaltern subjects, they became discardable. Much like the Israeli state’s systematic dehumanisation, with Palestinians lives reduced to security risks, obstacles, or collateral, Gachiakuta depicts a world where the subaltern are deprived of personhood, reclassified as waste, and their disposability is built into the machinery of order itself.

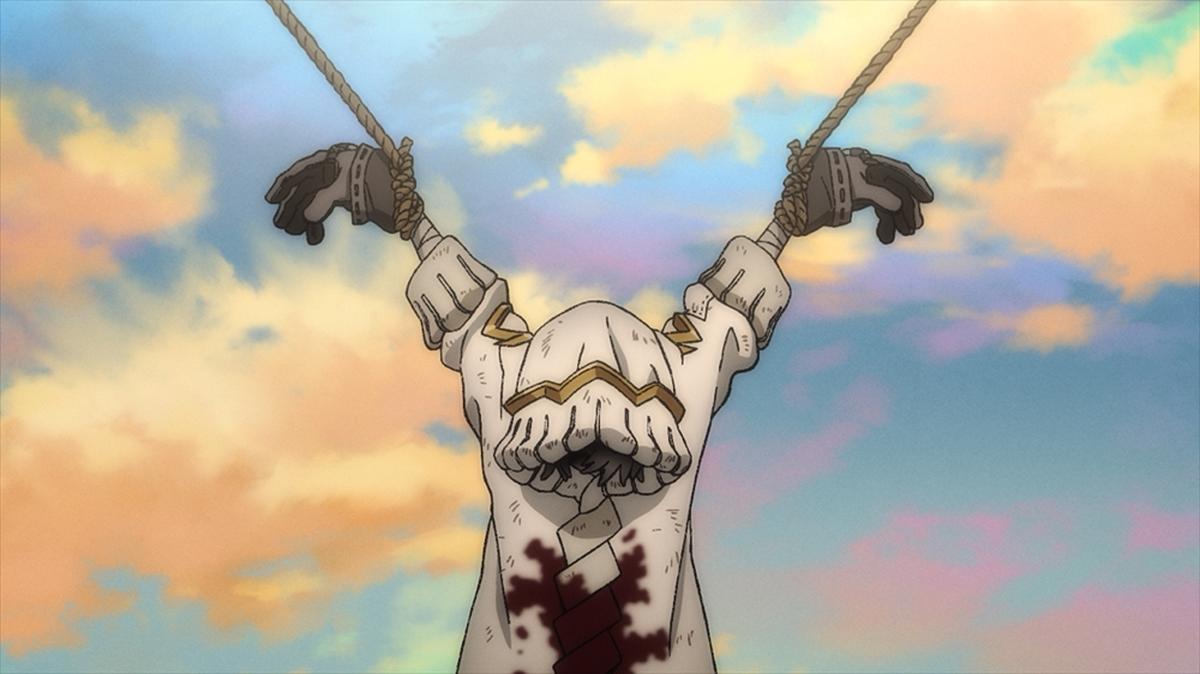

A still from ‘Gachiakuta’

| Photo Credit:

Crunchyroll

When Rudo is framed for a murder there is no trial worth mentioning. His skin is dirty, his hands are scarred, and his history is known. Guilt is automatically ascribed by lineage. The slum kid. The son of a murderer. The inevitable repeat offender. This kind of predetermined guilt has real-world echoes in the long global history of Indigenous children labeled as delinquents, of Dalits punished for crimes committed against them, of Palestinians tried in a system designed for their erasure. It’s not enough to be poor or from the “wrong” side of town — you also have to carry the suspicion of violence, of danger, and of inherent corruption.

Gachiakuta does not leave Rudo to rot, but arms him — both literally and figuratively — with a power drawn from that which has been discarded. Vital Instruments or “Jinki”, the story’s totemic weapons, are everyday objects imbued with memory, grief, and spirit. This reorientation from trash as detritus to trash as inheritance flips the colonial lens on its head.

Here, Gachiakuta gives identity back to the dehumanised. Restoring dignity to the castoff, animating the abject, breathing life into the corpse of the colonised subject — these are things that the empire has always feared. Rudo’s power as a “Giver” is a clever ontological statement. He becomes an anti-colonial artisan, forging weapons and meaning from refuse.

The story’s visual language amplifies this ethos. The graffiti-inspired designs and the grubby textures coalesce into a form of resistance that is not clean, or noble, or photogenic, but dirty and desperate and made from spare parts.

A still from ‘Gachiakuta’

| Photo Credit:

Crunchyroll

Anime has long smuggled sharp class critique into its storytelling. In Attack on Titan, the Eldians are walled-off, vilified, and turned into weapons. In Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, the Ishvalan people are victims of ethnic cleansing, their culture burned and bodies buried beneath the myth of national unity. Pluto, Naoki Urasawa’s reimagining of an Astro Boy arc, wrestles with who gets to decide what counts as human, while Cyberpunk: Edgerunners shows a city that chews up the poor and sells their rebellion back to them.

The main tension in Gachiakuta is between visibility and erasure. Between those who can afford to forget, and those who are remembered only as a cautionary tale. What the story ultimately suggests is that the act of naming the Other — of calling someone “criminal,” “subhuman,” or “trash” — is a prelude to disposal. But the response need not be assimilation. Rudo does not want to be accepted by the Sphere. He does not crave forgiveness. He wants something messier and more honest, like revenge and reclamation.

This furious vision in Gachiakuta isn’t entirely new, but it feels especially urgent at a time when resistance to oppression is being rebranded as terrorism, disruption, or disorder. This is a reminder of what every empire is trying to bury: the garbage dump never forgets.

Gachiakuta premieres on Crunchyroll on July 6 with new episodes weekly. The first two episodes of the series were made available to the author for review.

Published – July 04, 2025 06:45 pm IST